Teghan Simonton - The Yellow Jacket

Teghan Simonton - The Yellow Jacket The opioid crisis isn’t just a health problem.

It isn’t just a crime problem.

It’s a community problem.

That’s according to Karen Bennett, director of Human Services in Greene County. That’s the reason the county is officially expanding its overdose task force, modeling it after the successful coalition in the neighboring Washington County.

With the help of the University of Pittsburgh’s Overdose Prevention Research Program, the task force is moving beyond its current membership of a few elected officials, law enforcement and health professionals, to include community members with a variety of experiences.

“The purpose was kind of to collect data about our overdose deaths [in the county] and try to figure out a strategy to prevent our overdose deaths,” said Bennett.

According to the official list of invitees, 42 people have been invited to the new task force’s first meeting later this month. Included are professionals from academia, religious stakeholders and the “recovering community,” said Bennett.

One of the key additions, Bennett said, is the new Greene County Coroner, Gene Rush.

“The old coroner was on, but he was not very participatory,” said Bennett.

Indeed, last year, the Observer-Reporter entered into a lawsuit against the former coroner, Gregory Rohanna, for his refusal to release statistics about the county’s overdose rates. Rohanna lost re-election in November.

In the past week, Rush released information about last year’s overdoses, including gender makeup, age and types of drugs to the Obeserver-Reporter, leading the newspaper to drop the suit.

Bennett said Rush’s cooperation and transparency will be imperative to the success of the new task force.

“The difference is just a collaboration process, and he is one of the key stakeholders,” she said. “That position [the coroner] is one of the key stakeholders. He is working with families.”

Rush said he is looking forward to being a part of the group and providing his expertise.

“I’m going to be the statistical guy,” he said. “Information on types of drug deaths and drugs involved.”

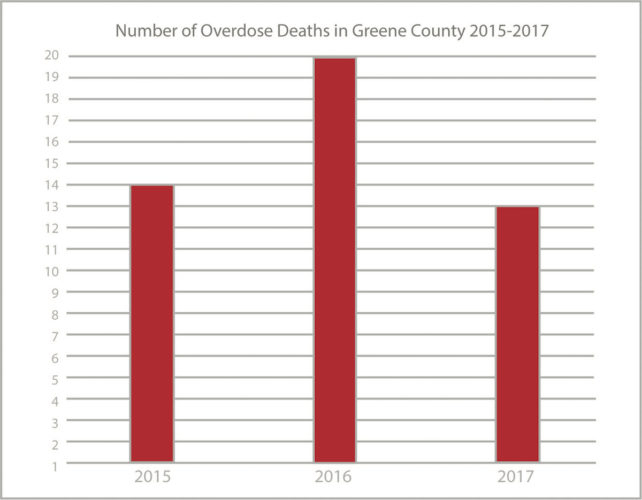

It was also reported that last year’s number of overdose deaths, listed on the official coroner’s report as “acute mixed drug toxicity,” was significantly lower than in previous years. Rush said the number of deaths dropped from 20 to 13, with drugs involved including heroin, fentanyl, codeine, cocaine and others. While it could be a result of year-to-year fluctuation and a small sample size, Rush was unable to speculate as to why the drop occurred.

“That’s strictly from [Rohanna’s] records,” he said. “There’s no way of knowing the reason for the drop.”

One of the purposes of the task force is to privately analyze this data and take in the perspectives of multiple interest groups. Bennett said meetings will be held with the understanding of complete confidentiality.

“It’s very important that when we talk about data, it remains in that group and in the context of that discussion,” said Bennett. “The opioid task force will release that data in the way they decide to share that information.”

Bennett said they are relying on the expertise of the University of Pittsburgh’s research unit. The Overdose Prevention Program has facilitated task forces like these with success across the state. Washington County’s program has achieved remarkable progress in a short amount of time, said Bennett, “but it takes all the key people involved to get where you need to go.”

That’s why the task force is becoming community-based.

Collaborating with stakeholders across the community will help the county focus its efforts, Bennett said. For example, the religious community will have its own goals, but now everyone can work together to achieve them. No one will be “isolated.”

“This thing is a community problem, and the strategies that you use have to address all aspects of the community,” said Bennett. “It takes all of the people to help or to volunteer.”