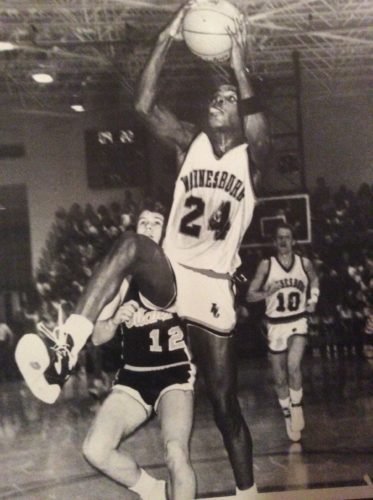

Photo Courtesy of Darrin Walls

Photo Courtesy of Darrin Walls How’s this for a picture?

Imagine a Saturday night at Waynesburg University. As is the case on most college campuses, many students who aren’t out partying will hang out in their room and watch ESPN. It’s March, so there’s a college basketball game on. The thought of such a small school like Waynesburg being one of the teams playing in that game sounds like a reach, to say the least. The idea of that game having Dick Vitale on the call? Not a chance. Yet 31 years ago, both of those things happened, and the game in question had the words “Final Four” attached to it.

The program at what was then Waynesburg College wasn’t just a regional powerhouse, like St. Vincent and Thomas More have been in the Presidents’ Athletic Conference recently. The Jackets were a force nationally, to the point where, in 1988, Vitale was alongside Tim Brando announcing Waynesburg College’s Final Four game against Grand Canyon on ESPN.

The Jackets, then a member of the NAIA, had the advantage of offering scholarships. Because of this, head coach Rudy Marisa scouted the finest talent in school history, led by three-time All-American and Waynesburg’s all-time leading scorer Darrin Walls. With players like Walls (734 points), Harold Hamlin (571 points) and Rob Montgomery (593 points) leading the way, the Jackets were a national powerhouse. Between 1983-1988, Waynesburg went 131-21 overall and 70-1 at home, winning five straight District 18 championships, with a sixth coming in 1989.

“We had some players that could really play who could have went anywhere, Division I schools or wherever,” Walls said. “Growing up with [center] Rob Montgomery, [forward] Harold Hamlin, we played against Jerome Lane and all the Pitt players, and we always did well.”

In fact, Walls said Lane was among the Panthers players who tried to recruit him to leave Waynesburg and play in the Big East. But Walls, who was getting letters from NBA teams, saw no reason to leave Greene County. Hamlin, a year ahead of Walls, won the Pittsburgh City League title with him at Peabody High School, and the two became college teammates in the fall of 1985 (there, they played against Montgomery, who graduated from Taylor Allderdice).

Hamlin, a gifted talent in his own right, believes he would have joined his childhood friend in the 2,000-point club if not for an ACL tear in December of his sophomore year.

The climax of that era of Jacket dominance was in March 1988. Waynesburg took a 32-game winning streak into its NAIA semifinal matchup with Grand Canyon, led by head coach Paul Westphal, who would be leading the Phoenix Suns in the NBA just four years later.

On the surface, there was little reason to believe this orange and black locomotive would halt. The Jackets hadn’t lost since the first game of the year— a 119-112 shootout against Bluefield State played with a pace that would foreshadow that Final Four game.

Waynesburg then emphatically regrouped, winning 32 straight with 23 of those wins coming by double digits. The streak eventually led Waynesburg to its fifth straight District 18 championship with an 85-72 win over Westminster. The Jackets promptly beat Franklin Pierce (N.H.), Minnesota-Duluth and Dordt (Iowa) by a 15-point average to get to the Final Four.

Grand Canyon’s style of play was a “mirror image” of Waynesburg’s, and what ensued was a back-and-forth classic with a wild—and gutting—ending.

The season

Expectations were high for Waynesburg going into the 1987-88 season.

With a young roster in 1986-87, the Jackets won District 18 for the fourth straight season and went to the NAIA Elite Eight.

After opening night, however, Waynesburg was 0-1.

Right away, Hamlin remembers, Marisa let the team know that things were about to change.

“That first game of the year that we lost, that made us focus,” Hamlin said. “Coach made us focus, too, because I think he cut about four people after that game.”

It wasn’t uncommon for Marisa to weed out players who he felt were dead weight to what the Jackets were trying to accomplish. Point guard Shawn McCallister, who transferred to Waynesburg after his sophomore year when Alliance College dropped its basketball program, remembers Marisa sending two players home from Kansas City for missing curfew. The program was built on structure, Marisa’s former players say, and anything that hurt the structure was removed.

“If we had a meeting at 12, you better be there at 11:45,” Hamlin said. “Not 12. Not 11:55. He didn’t want anybody walking in when he was about to start his meeting. Because sometimes he would start early, and if you weren’t there, there’s a good chance you were getting cut.”

From the perspective of Marisa, the first game of the season was taken too lightly by some of the team.

“I knew we had a talented team, and maybe the players might have assumed that opener was going to be not too tough for them,” Marisa said. “But after losing it, they realized we still had to work hard the rest of the year, and they did that.”

The Jackets worked, and they won. Waynesburg identified as a fast-paced team that would sometimes, such as against Bluefield State, give up a lot of points, but compensate by scoring a lot more. The goal, former assistant coach and current Athletic Director at Waynesburg University Larry Marshall remembers, was to get a shot off within three seconds if the other team scored.

That season, Waynesburg scored 100 or more points 12 times. The Jackets had the talent to win the school’s first national championship in any sport since the football team did it in 1966, and as Hamlin remembers, they knew it.

“Even though we’re a small NAIA school, we thought we were the best in the country,” Hamlin said. “We strived to win it all. In District 18, we kind of got tired of winning, because we just won that every year. We were looking for something bigger and better.”

The Game

Playing in high-pressure games wasn’t out of the ordinary for Waynesburg. For the past few years, Waynesburg had played in four district games and in 1987, reached the Elite Eight of the NAIA tournament. In addition, every Waynesburg home game, regardless of whether it was in November or March, felt like a big deal.

“If the game started at eight and you weren’t here by 6:30, you didn’t get in,” Marshall said. “The place was packed…and it wasn’t just college students; it was townspeople. They had a booster’s club at the time and everything, and the townspeople all showed up to everything. It was a small campus with a big atmosphere.”

Even if you got to the games early, Walls said there would always be a line to get in.

“Crazy,” Walls said about the atmosphere. “It was crazy. The line would be down to Martin Hall to get in [the gym]. They’d be sitting on the steps; that’s how crazy it was. Hours before. The atmosphere was unbelievable.”

So, while the Final Four at Kansas City’s Kemper Arena was a different type of pressure, the Jackets were used to it.

“We were veterans,” Walls said. “We were used to winning. We were used to playing good teams, and we thought we were the best team in the country.”

While Waynesburg wasn’t intimidated by the aura, the players knew that it was unlike anything they had ever been a part of. Backup point guard Kevin Lee remembers the bright TV lights by the baskets. Hamlin recalls the unusually large amount of TV timeouts disrupting the rhythm of the game. For McCallister, he’s proud to have simply been a part of it all.

“It was an amazing time, it really was,” McCallister said, who is now the athletic director at Steele Valley High School. “Looking back on it, we had an opportunity to talk to Dick Vitale. Just the atmosphere in general [was great] but to get on the court with a team like Grand Canyon…their style of play and our style of play really meshed, and it was an exciting game. … It was excellent basketball to be part of.”

Grand Canyon’s identity can be figured out just by looking at the final scores of its road to the Final Four (103-75, 101-95 and 99-96). The Antelopes, much like Waynesburg, played a fast-paced style of basketball and knew how to put the ball in the hoop.

“They were just like us, pretty much,” Walls said. “It was kind of shocking to see a mirror image of a team just like us.”

It was apparent from the beginning that defense wouldn’t run the night. After a back and forth first half, Grand Canyon led, 47-44.

The ending

Marisa doesn’t remember the first 35 minutes of the game.

All he remembers are the final five minutes. He still replays them in his head.

Late in the second half, it looked like Grand Canyon might pull away, as the Antelopes led by nine with four minutes left. But the Jackets started a comeback under the direction of Walls. The junior finished with 32 points, and his free throw with less than a minute left tied the game.

“At that stage of my career, I felt like I was unstoppable,” Walls said. “We had some other people that were capable of [scoring], but they’d get the ball to me, and I was the scorer. So, I was trying just to carry my team on my back and do what I usually do, [which was] put the ball in the hoop.”

With 41 seconds left, Waynesburg had possession, and held it for 26 seconds before Marisa called a time out. The rest of the game, as Walls remembers, “took forever.”

The plan coming out of the timeout varies depending on who you talk to.

Marisa remembers the plan being to hold the ball for the last shot. Walls said it was to take a shot with enough time on the clock so the Jackets could pick up an offensive rebound if it didn’t go. Marshall said Marisa told Walls to drive to the basket, but Hamlin advised his childhood friend to take a jumper. Whatever the conversation entailed, it seemed as if there were only two possible outcomes: either Waynesburg would score and move on to the national championship game or this NAIA classic would move to overtime.

With 12 seconds left, Walls got the ball behind the top of the key.

He moved left, and with eight seconds left, took an uncontested shot.

Walls—a 48 percent shooter from the field that season—thought it was going in, and so did Hamlin.

“Oh yeah. I say nine of 10 times, he’d have made that shot,” Hamlin said. “We all had confidence in him making it or other teammates to make the shot.”

The ball hit off the front iron. Grand Canyon grabbed the rebound, pushed the ball down the court and with two seconds left, Mike Ledbetter attempted an off-balanced layup that missed.

Waiting for the rebound however, was Rodney Johns who, according to all Waynesburg accounts, was Grand Canyon’s best player. Johns banked the ball in off the glass and into the hoop and the closest opportunity Waynesburg had for national championship went by the wayside.

The Aftermath

The Yellow Jackets were shocked.

ESPN’s cameras captured Montgomery lying on the ground, and an obviously dejected McCallister picking himself up from his knees.

Walls remembers picking teammate Ron Moore up from the court.

“It was so surreal, that you just didn’t believe that it came to an end that fast,” McCallister said. “[We were] very deflated at that time. I think when you’re a college student, you don’t really understand until later in life how lucky you were to be a part of something that great.”

While Waynesburg still had Walls for another year and won District 18 once again, the Yellow Jackets would never get back to the Final Four. By the early 90s, the college moved from the NAIA to the NCAA, and although the program still had success with Marisa coaching until 2003 and ending his career with 565 wins, Waynesburg never got back to where it was in 1988 and never recruited a player like Walls or Hamlin again.

“We gave up our scholarships at that point and went Division III, so everything changed,” Marisa said. “We couldn’t possibly have the same kind of players… we played teams that were also Division III, so it was still ‘even Steven.’ But to compare [DIII] to the old NAIA, there were more scholarship players, and it was just at a higher level.”

While the team was disappointed, Marshall said in the post-game locker room, nobody was feeling sorry for themselves.

“It wasn’t by any means a ‘crying fest’ or anything,” Marshall said. “Because to go the way we did to experience what we had was something that I know they’ll remember all their lives.”

Hamlin’s memory of the post-game locker room is a little more light hearted than one would think.

“The funniest thing about it was as soon as the game ended, we had to take a piss test,” he said. “I know I did, so that was kind of odd. I wasn’t too happy about that, after losing like that, then they tell you to pee in a cup.”

Later, in the team’s hotel, with a meaningless consolation game looming, Walls remembers talking with some of his teammates, including Hamlin and Moore. The team talked about the game, and acknowledged that it wasn’t their time.

“ESPN was replaying the game on TV. That was a little shocker, we watched a little bit of it. I think it helped heal a little bit, to be truthful,” Walls said.

While the golden age of Waynesburg basketball didn’t climax with cutting down the nets in Kemper Arena, Hamlin, Walls and the rest the team will always be grateful for what they accomplished.

“I take a lot of pride in it,” Hamlin said. “We had a long winning streak in home, and just for a lot of guys that I know that I played against that I played with in high school, to come to a school and come together, and put Waynesburg—I mean they were already on the map, I think locally, but I think we put Waynesburg on the map nationally. And that’s something we can always take with us.”